The excavations have exposed the marble steps leading to the edicule and a coin deposit, which were most recently minted during the reign of Emperor Valens (364–378).

Jerusalem’s Church of the Holy Sepulcher, one of the holiest places in the world for Christians and an important pilgrimage site since the fourth century, is revealing more of its secrets. Ongoing archaeological investigations related to the restoration of the basilica’s floor are at a turning point, with many surprises coming to light.

The latest — and one of the most significant — findings emerged during the investigations conducted during the second half of June in the area in front of the edicule — the small shrine/temple that encloses the tomb of Jesus located in the center of the rotunda, under the big dome of the basilica.

The excavations have exposed the marble steps leading to the edicule and a coin deposit, which were most recently minted during the reign of Emperor Valens (364–378). This allows archeologists to accurately date the early Christian edicule to that period.

Located in the northwest quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem, the Church of the Holy Sepulcher is believed to be the site of Jesus’ crucifixion, death, and resurrection. Constantine the Great built the first church there, dedicated in about 336 A.D. His mother, St. Helena, was believed to have found a relic of the cross of Christ’s crucifixion on the site. Almost 300 years later, the Persians burned the church down, after which it was restored, destroyed again, and restored once more. The Crusaders in the 12th century undertook a rebuild of the site, which included a chapel in St. Helena’s honor. Since that time, frequent restorations and repairs have taken place.

Other discoveries that emerged during the first year of work involve the remains of the early Christian liturgical basilica — a construction site of the Constantinian age — and the foundations of the northern perimeter wall of the complex and the water drainage system in the northwestern area of the rotunda, next to the edicule.

Archeologists also discovered that the quarry in the southern part of the rotunda, an area outside the city walls, was used as a cave. The cave was dismantled in the first century B.C. and transformed into an agricultural and burial area.

“We are gaining an in-depth understanding of the entire stratigraphic sequence [the order and position of layers of archeological remains]: from the use of the quarry in pre-Constantinian times to the restoration work during the British Mandate [for Palestine],” Francesca Romana Stasolla, the leader of the team from the Department of Ancient Sciences at the University of Rome Sapienza responsible for the archaeological research, told CNA in an interview. Stasolla said her team can now trace “the entire material history of the religious complex.”

The recent plan to restore the Holy Sepulcher’s floor, along with concurrent archaeological, structural, and waterworks investigations, was determined by the three Christian churches responsible for the basilica: the Greek Orthodox, the Roman Catholic (Custody of the Holy Land), and the Armenian Apostolic churches. Operations are coordinated by the Common Technical Bureau, an office of experts representing the three communities.

The University of Rome Sapienza is responsible for the excavations. In addition to archaeologists from the Department of Ancient Sciences, the team also includes engineers, historians, philologists, geologists, paleobotanists, and archaeobotanists from the same university. The interdisciplinary team addresses, analyses, and interprets everything that emerges during the excavations.

Specialists from the Venaria Reale Conservation and Restoration Center are handling the restoration of the floor. Two engineering companies from Italy — Manens, based in Padua, and IG Ingegneria Geotecnica, based in Turin — are also involved in the project overseeing infrastructure and utilities such as the electrical and water systems.

A New Chapter

The recent work officially began on March 14, 2022, with the removal of the first paving stone; preparatory phases were initiated as early as 2019 but were slowed down by the pandemic.

What has been uncovered so far will make it possible to write — and rewrite — some pages of the basilica’s history. For instance, before it was a church property, the land was used as a quarry and for farming.

“We have identified the presence of at least two definite species — olive and grapevine. This confirms what it says in some passages of the Gospels,” Stasolla told CNA.

“The various discoveries emerging as the work progresses will enable us to describe architecturally something that was not known before. They will also help us understand the intermediate periods — such as between the early Christian and medieval phases, and between the medieval and modern phases, about which we know very little,” said Stasolla, who explained that this is due to a lack of sources (especially during periods of reduced pilgrimages) or when accounts are less descriptive.

The Edicule Continues to Amaze

From June 19–27, the area in front of the edicule and the edicule itself (the structure raised over the place of Christ’s tomb) was closed to allow the removal of the floor and archaeological investigations.

Seven days and nights of uninterrupted work revealed the funerary area in the same area of the edicule and, in particular, the first “monumentalization” of the edicule in the early Christian period. (“Monumentalizing” is a term used to describe commemorating or immortalizing something with a monument.)

In fact, according to Stasolla, what the team of archaeologists discovered was a “double monumentalization,” which they didn’t expect because it occurred at a very close temporal distance.

“We were able to document an initial phase of monumentalization from the beginning of the fourth century and a second phase from the end of the fourth century,” Stasolla said, which she explained was confirmed by the discovery of a coin deposit, with the last emissions being those of Emperor Valens.

“In the first phase, there were three marble steps leading to the venerated tomb, which we found. In the second phase, there were only two steps because the floor was partially raised,” she added.

These discoveries align with the oldest iconography from the fifth century and the description by the famous pilgrim Egeria, whose diary is one of the most important early sources on early Christianity. Egeria is believed to have arrived in Jerusalem a few years after the conclusion of the second phase of monumentalization, sometime between 381 and 384 A.D.

A statement from the Custody of the Holy Land said the restoration of the floor inside the edicule revealed “part of the bottom of a burial chamber similar to those found in the northern portion of the rotunda, filled in and arranged to encourage pilgrims to visit since the early Christian period.”

“In the edicule,” Stasolla specified, “the medieval floor covers a burial chamber. The monumentalization, already from the early Christian period, serves to monumentalize a tomb.”

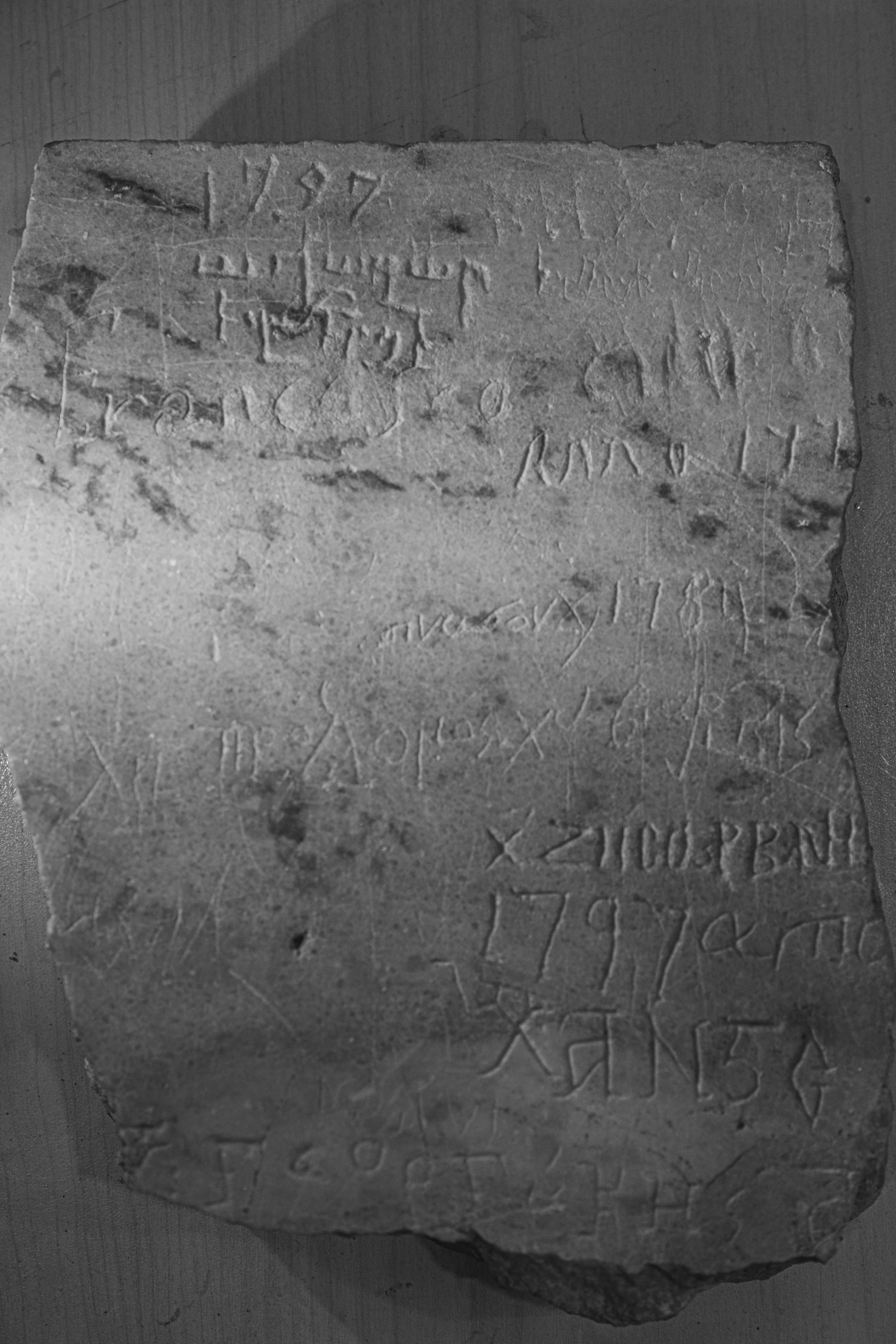

In the antechamber, called the Chapel of the Angel, traces of the initial arrangement of the monument for liturgical purposes and remains of the sixth-century arrangement of the edicule were found, including inscriptions by pilgrims in Latin, Greek, and Armenian (18th century).

According to Stasolla, outside there was a large polished floor made from local stone and other materials, traces of which were found in the preparation mortar.

Other Discoveries

During the first year of work, some interesting archaeological elements were discovered and reported in periodic updates signed by Stasolla and distributed by the Custody of the Holy Land. For instance, a recent update on July 7 focused on information related to excavation work in the area in front of the edicule of the Holy Sepulcher.

Strasolla highlighted other interesting discoveries. In the northern area of the ambulatory, remains of the early Christian liturgical basilica were found, already known from historical sources, which contributed to completing the plan of the early Christian complex.

A small portion of the apse had already been discovered under the Greeks’ Catholicon (the name given to cathedrals and monastery churches by the Greek-Orthodox), and in the chapel of St. Vartan.

“In the coming months, we will continue archaeological investigations in that area to complete the excavation of the apse,” Stazolla said.

Additionally, in the northern nave of the basilica, the excavations revealed the construction site of the Constantinian age, and the foundations of the northern perimeter wall of the complex commissioned by the first Christian emperor.

According to a Custody of the Holy Land press release, in the northwestern area of the Rotunda, next to the edicule, “a tunnel has been intercepted, partly already highlighted in previous investigations, which descends vertically next to the edicule for a depth of 2.80 meters [9.18 feet] and then continues horizontally to the north.” This is an important element in the study of architectural aspects of the basilica, especially in relation to excavation stratigraphy and its connection to the entire water drainage system.

The Timeline

The excavation continues to proceed in a way that allows for the regular conduct of liturgical ceremonies and the flow of pilgrims.

“We have managed to close the northern half of the north nave, complete the entire rotunda, and half of the ambulatory,” Stasolla told CNA. “In these weeks, we are finishing the southeast area of the rotunda. We are adhering to the project timeline and expect to deliver the work on schedule.”

They hope to finish the work by the end of 2024.

The excavation work is conducted continuously, day and night, and the processing of the materials uncovered is conducted in real time between Jerusalem and Rome. All the data processed during the excavation are entered into a database specifically created for the project and linked to various historical and archival sources.